“The best predictor of beginning reading achievement is a child’s knowledge of letter names" (Adams, 1990).

I am sure that you have heard this statement. It is one of the most popular quotes about letters, and it is routinely shared with educators in professional development sessions, on websites, and in curricula. Unfortunately, some have interpreted this to mean that teaching children to name letters in isolation is a straight path to literacy. If only that were true! Teaching children to say the names of letters will not be enough. Although it can be helpful, children need to know letter sounds and how to use letter sounds to become readers and writers (Lonigan & Shanahan, 2009).

I see schools and teachers drilling letter names all the time. In fact, I was recently in one school watching kindergartners as they named random letters flashing up on a Smart Board, “D, f, g, H, z, s.” “They have to practice for the state test,” their principal explained. At times, educators have gotten so caught up in counting the number of letters children can name that one group of researchers laughingly called letter naming the “Ouija board” of literacy achievement—a magical measure—know the number of letters children can name, and you can peer into their literacy futures (Invernizzi & Buckrop, 2018). The number of letters a child can name is so closely associated with future reading achievement because that number is also related to other factors that drive reading achievement (Share, 1995).

Let’s take Devon, a kindergartner who can name 36 upper- and lowercase letters in October. Before entering kindergarten Devon listened to books his parents read to him each night, participated in an array of experiences (e.g., trips to the zoo, museums, preschool playgroups), and attended a high-quality preschool focused not only on literacy skills but also on social-emotional development and oral language. Due to these experiences, he has a rich oral vocabulary, an awareness of sound units in language (e.g. phonological awareness- hearing rhymes, hearing beginning sounds), knows some letter sounds, and he has some understandings of how print works (e.g. left-to-right, top-to-bottom). So, Devon’s ability to name letters is really just the tip of the iceberg in terms of his knowledge of literacy and the world.

In this blog, I will describe different types of letter knowledge, pinpoint the “Big Picture” or system within which letters operate, identify the most important type of letter knowledge, suggest a routine for introducing new letters, and share ways to model the use of letters.

Letter Naming Is Only One Type of Letter Knowledge

Frequently people have misunderstandings about the complexity of letter knowledge. I run into parents all the time who say, "Listen, she knows her letters—she can sing the alphabet song!" Of course, singing lyrics to a song does not mean a child really knows all she needs to know about letters. Many children sing nursery rhymes and other tunes, but cannot read the words.

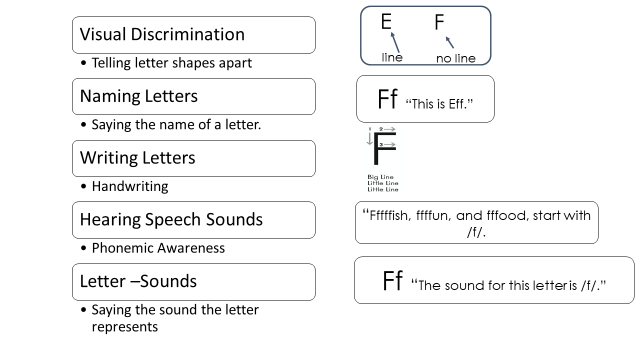

Letter knowledge is multifaceted and takes time to learn. From my perspective, there are at least five different letter skills that children need to become readers and writers. These skills include the following:

- Visually discriminate letters (Tell the letters apart).

- Name letters (Know the names of letters).

- Write letters quickly and accurately

- Connect sounds to letter forms, (Know the sounds the letters represent)

- Hear sounds in words (Orally identify that sun, sip, and sail start the same)

The first and easiest skill is visual discrimination (Willingham, 2017). For this level children must be able to visually distinguish the shapes and essential features of each letter. For instance, they must be able to distinguish an E from F or an f from a t, paying attention to subtle visual details (e.g., The E has an extra line at the bottom. The t has a cross. The f has a hook at the top and a cross). Visually distinguishing letters also requires children to pay attention to direction because some letters actually change if rotated or flipped (such as b, p, d).

The second skill, one that develops alongside visual discrimination, is learning the names of letters. A child can tell you “This (Bb), is the letter ‘Bee.’” The third skill, writing letters correctly, takes high-quality handwriting instruction and an understanding of how to best support children’s fine motor development. This brings me to the fourth skill, connecting letters and sounds. We call the sounds that letters represent phonemes or speech sounds. As I will detail below, letter-sound knowledge is critical for decoding and spelling.

Surprisingly, the most difficult part of letter knowledge is not actually naming letters or learning letter-sounds, but hearing the individual speech sounds that letters represent (Willingham, 2017).

In order to connect speech sounds to visual letter symbols, children must be phonemically aware or hear sounds. This is an oral skill and it means that a child has the insight that words can be broken into speech sounds or phonemes. For example, a child who is phonemically aware can listen and tell that the words bat, big, and boy all start with the same sound or hear that bat has three sounds /b/ /a/ /t/. Without an awareness of these sound units, trying to learn letter sounds usually doesn’t go too well, because phonemes are the basis of the system.

Children Must Understand the “Big Picture”

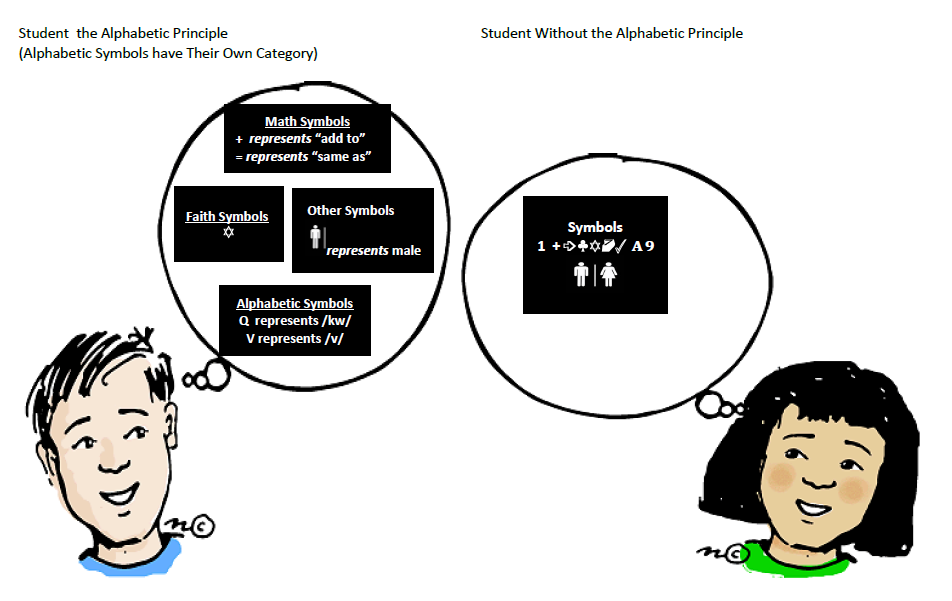

As children are learning the details of letter names and sounds, they must understand the system, which we call the alphabetic principle. Quite simply, the alphabetic principle is that visual letter symbols are used to represent speech sounds or phonemes. This is the system or the organization of our English alphabet—symbols represent speech sounds. In some written languages, the written symbols represent whole words or even syllables.

This little cartoon shows two children, one with the alphabetic principle and one without. As you can see, the girl groups all of the symbols together without understanding what each represents. There are numbers, icons, letters, and faith symbols. The boy has differentiated symbols and understands that letters are special “literacy” symbols representing speech sounds.

Letter-sounds are More Important than Letter Names

When a child can name a letter, he can tell you the label we use for the letter. For example, he can tell you the name “Tee” for Tt. However, letter names are not actually what we use when we are decoding. The essential information is the letter sound. So, if I am reading and come to the word tap, I would not say “Tee” but the sound /t/.

Letter-sounds are what is most critical. It is letter-sounds that children must quickly and accurately access to decode words. - Heidi Anne Mesmer

In the US, we always teach both the letter name and the letter sound because letter names sometimes help children with sounds. Ever wonder why children who are learning a letter like Ww will tell you that it makes the sound /d/? Where do they come up with the sound /d/? This is because children sometimes use the letter names to help them with sounds and the name of Ww starts with a /d/. For many letters, the names can actually help children learn sounds. Letters like, Bb, Dd, Jj, Kk, Pp, Tt, Vv, Zz, have the target sound at the beginning of their names (e.g. “Bee” /b/, “Tee” /t/) and others like Ff, Ll, Mm, Nn, Rr, and Ss have the target sound at the end of their names (e.g., “Eff,’ /f/, “Ess” /s/). Letters like Ww, Yy, Qq, and Hh do not have helpful information in the name.

Routines for Introducing Letters Support Complete Learning

To make sure that you consistently present both letter and sound, use a routine.

Point to the letter, say its name and the sound, and then demonstrate how to write the letter. Sometimes teachers leave off the sound, thinking that it might be too hard or, like the principal at the beginning of the blog, ignore letter sounds because they are not "tested." Letter sounds are so crucial that we always present them when teaching a letter, even if we think it might be “too hard.”

When you say the sound of the letter, do it in isolation but try not to add extra sounds. For example, say /z/ or /f/. It is easy with stop consonants to add a little too much “uh” to the sound like this “Buh, Kuh, Duh.” Although it is technically impossible not to have a little bit of an /uh/ sound on stop consonants, try not to add too much.

After naming the letter and sound, help children find it in text, or around the room, or in the names of their friends!

Really knowing a letter means seeing it everywhere (Jones & Reutzel, 2012).

Modeling How to Use Letter-Sounds Demonstrates the Reason We Teach Them

One of the most common mistakes that teachers make in letter instruction is believing that it is all about letters. They teach children to memorize letter names and letter sounds but then find that children cannot use that information, or do not understand the larger system within which letter-sound information operates. Some rhetoric entangled teachers in the false choice of whether to teach letters in isolation or within context. We must do both.

For children to understand how to use letters, we must model real reading and writing every day. This means using large books during whole-class shared reading. During shared reading, teachers point to words, letters, and sentences. It means writing a message together with students during a morning meeting. For example, a teacher I know showed children how to use their new knowledge of the letter Ss as she wrote this message: “Today we will see the seals at the zoo.” Each time she emphasized the sound /s/ and then asked an eager child to come up to the chart to write an s at the beginning of the words see and seals.

Another wonderful practice to helping children learn how to use letter sounds is using “little books.” These child-friendly books give children a chance to navigate text and use letter sounds after watching their teacher’s modeling. Without the repeated illustration of how to use letters in books and writing, letter learning remains inert and boring. The whole purpose of learning letters is to access the messages of authors or write our own!

It is simple to “check the box” by teaching children letter names, but it can provide a false sense of effectiveness. Yes, children start with the letter names, but they must learn and use letter-sounds, and do so quite efficiently. I like to say that you could wake a child up in the middle of the night and show them a letter, like Vv and they could tell you the sound. That level of automaticity is exactly what children need as readers and writers. Don’t get pulled into the trap of just teaching children to say the names of letters, help them become fully literate by teaching letter sounds, handwriting, phonemic awareness, and how to use letters.

New Workshop: Accelerating Alphabet Learning

We know that emerging readers must learn letters, letter sounds, and how to manipulate letter sounds in practical, authentic ways. We invite you to join us for our NEW workshop, Accelerating Alphabet Learning: 8 Effective Strategies. Join me as we explore eight ways to incorporate alphabet learning throughout the day in school and at home. Together we'll examine the challenges of letter instruction and use this information to help effectively support your emerging readers. Register now, for this virtual workshop taking place on Thursday, April 29 at 4 pm EST and you'll also be entered for a chance to win an autographed copy of my book Letter Lessons and First Words: Phonics Foundations that Work. Space is limited, so be sure to reserve your spot today!

References

Adams, M. J. (1994). Beginning to read: Thinking and learning about print.

Invernizzi, M., & Buckrop, J. (2018). Reconceptualizing Alphabet Learning and Instruction. Pivotal Research in Early Literacy: Foundational Studies and Current Practices, 85.

Lonigan, C. J., & Shanahan, T. (2008). Executive Summary Developing Early Literacy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel A Scientific Synthesis of Early Literacy Development and Implications for InterventionExecutive Summary of the report of the national early literacy panel.

Share, D. L. (1995). Phonological recoding and self-teaching: Sine qua non of reading acquisition. Cognition, 55(2), 151-218.

Willingham, D. T. (2017). The reading mind: A cognitive approach to understanding how the mind reads. John Wiley & Sons.

Jones, C. D., & Reutzel, D. R. (2012). Enhanced alphabet knowledge instruction: Exploring a change of frequency, focus, and distributed cycles of review. Reading Psychology, 33(5), 448-464.